Bubbles. Innocuous you think. Beautiful. The delight of children everywhere. Transparent spheres that refract light, drifting with improbable delicacy – hinting at rainbows – until the moment of their demise. And even demise is too strong a word. No more than an eye-blink between existence and non-existence. Gentle. No fuss. No more trace of their passing than a slight soapy stain on a piece of cloth or rapidly evaporating smear on the skin.

But this is just what bubbles want you to think. Letting your imagination expand and soar with them. Inviting you to see through them to whole new worlds of possibility.

Before they bring you down. Tear to shreds every drifting dream and flight of fancy you had invested in them. Leave you broken and broke, clearing muck from a sty while your children suck on rags and strips of old leather, wondering when they’ll next taste meat or fruit or even a turnip.

***

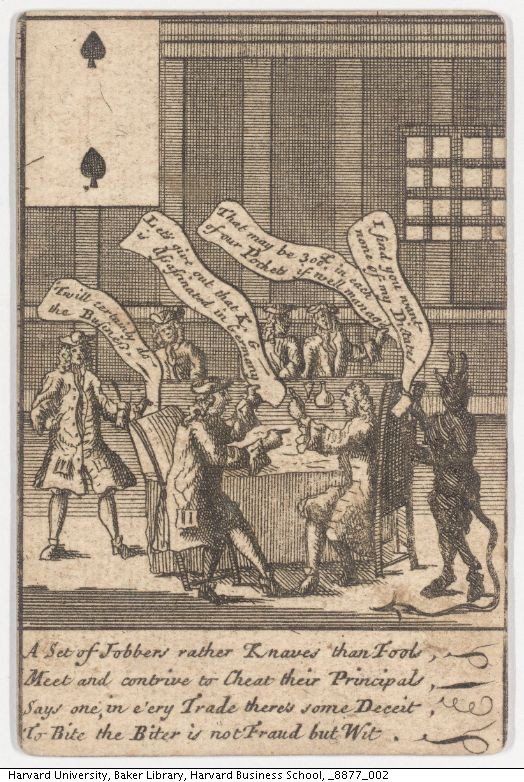

The South Sea Bubble of 1720 was one of the first but by no means the last or the worst of capitalism’s great bubbles. As with all the others, it made some rich and impoverished many. In a single year, obsessive trading in the stocks of Britain’s South Sea Company increased the price from just over £100 to almost £1,000 per share. Before 1720 was out, the price had plunged to well below its starting-point.

The South Sea Company, founded to consolidate and reduce state debt and to have a monopoly trade in the South Seas – the Spanish-controlled territory of Latin America –, had managed to disguise the fact that it could not turn a profit on either venture. The former because the dividend returns promised to investors outstripped the interest the Crown was prepared to pay. The latter because, for most of the life of the South Sea Company, Britain was at war with Spain and – consequently – the chances that Spain would grant extensive trade rights within its own sphere of influence to a British company were, shall we say, remote.

None of this stopped the directors of the company talking up the stock price. Free trade agreements would soon be signed with the Spanish. Mexico would give all the gold of their mines for cotton and woollen goods from England. It didn’t stop the company’s directors issuing new shares with promises of dividends to keep the upward spiral of the share price spiralling upwards. Nor did it stop them from profiting from straightforward insider trading, buying up public debt before a new tranche was authorised for sale to the Company.

Members of Parliament were bought by the Company. Nobles purchased shares on favourable terms. Even the King’s mistress invested. At the height of the bubble, people could barely enter Exchange Alley, the press of the crowd seeking to trade in South Sea Company shares was so great.

The bubble brought share trading into disrepute. Traders and investors alike were seen as venal and corrupt, seeking something for nothing – the solid something reflected in the bubble’s shimmering surface.

When the bubble finally burst, all of London rose in fury. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, John Aislabie, up to his neck in shifty deals and profiteering, was expelled from the House of Commons and made a guest, at His Majesty’s pleasure, in the Tower of London. Charles MacKay, in Extraordinary Public Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, reports that the Viscount Molesworth called for the ancient Roman punishment for children who murdered their fathers to be applied to the directors of the company.

They adjudged the guilty wretch to be sown in a sack, and thrown alive into the Tyber. He looked upon the contrivers and executors of the villanous South Sea scheme as the parricides of their country, and should be satisfied to see them tied in like manner in sacks, and thrown into the Thames.

He had the right punishment, but the wrong culprit. Why did no-one call for bubbles themselves – those globular seducers, the schemers behind the scheme – to be tied in sacks and drowned in rivers?

***

My two boys have bathed together for most of their lives, despite the four year difference in their ages.

They invented a bathtime game where they would sink down as low as they could and stick their pointed little knees out of the water. These would become the islands of an uncharted sea. Many action figures and lego men were brought to grief on the shoals of these slippery, treacherous islands which sank and rose and sank again with vindictive glee.

On occasion, for extra hilarity, one of the boys would duck-dive under the water, sticking his infant buttocks up above the surface. The south islands, as they became known, didn’t do anything except show themselves for a short time and then disappear as whichever child owned the landmark in question surfaced for breath. But the mere appearance of the south islands was the automatic culmination of whatever submarine battles they had been waging, and shortly after they surfaced bathtime inevitably dissolved in fits of laughter.

Until one day, the youngest’s south islands emitted a sulphurous blast into the air and then released a “south sea bubble” from below the water after he had turned himself right way up. His older brother – already becoming self-conscious and private – stepped out of the bath and, taking a towel, went to his room to dry himself and put on his pyjamas behind a closed door.

They never bathed together again.

***

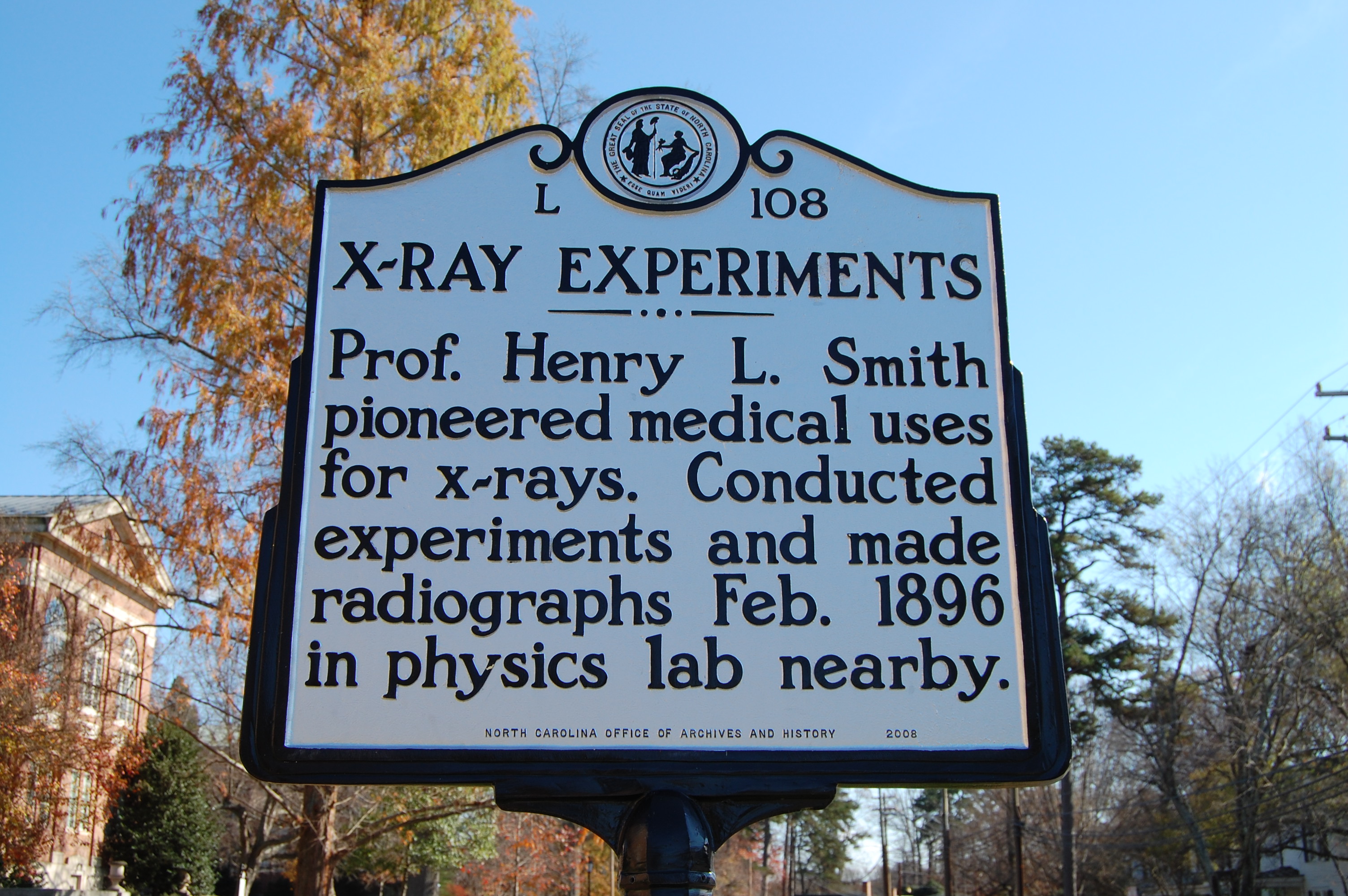

And even now bubbles are conspiring against you. They want what you have – your wealth and security – and they will have it. It’s only a matter of time. They have a plan to bring down the atmosphere on the heads of all of us and of those yet unborn. Bubbles of methane locked in the permafrost can feel a long thaw coming. Bubbles of that astonishingly effective greenhouse gas buried far beneath the bitter cold of the Arctic Ocean know that they will soon float free.

To ride the currents of a warming world, to soar again and take their rightful place alongside the beautiful, terrible, invisible bubbles of carbon dioxide we have been so heedlessly releasing into the sky. They will meet up with those molecules of carbon and oxygen that have been bearing aloft our dreams of unending riches ever since we learned how to liberate them from dense seams of coal and the sludge of oil. Then together they will show us, these bubbles, who is really in charge.

File under: sowing the wind | the madness of crowds

(Picture source: Harvard University Library)