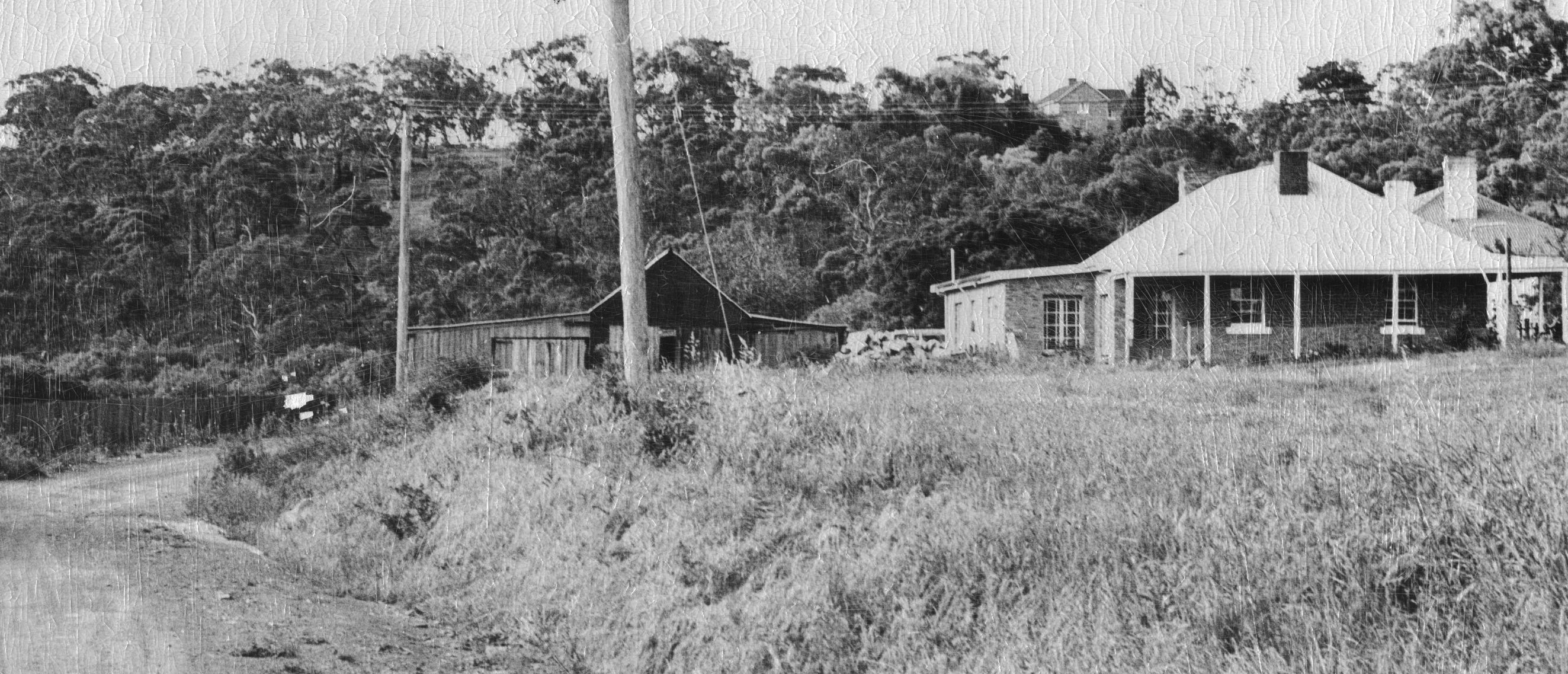

The house at 3 Marlborough Street, Pontville, Tasmania, is the first I really remember living in. We moved there – that is, my mother, father, elder sister and me – when I was two and lived there for another eight years, during which time I acquired two more sisters and a brother and our family traded up from a Datsun 120Y to a Datsun 180B. We left the house – and the state – before my tenth birthday and moved to Albury, on the mainland, where my father took a position with the newly-opened newsprint mill on the outskirts of town.

The house in Pontville was a tiny red-brick cottage with a lean-to bathroom and septic tank in the back yard. Built in the early nineteenth century, it had been home to the Governor of the gaol that once stood on what was then, and still is now, the vacant block opposite. When I was a kid, of course, I fit inside the house perfectly, but the scale of it was, in fact, alarming. It looked like a slightly scaled-down version of a real house, or a stupidly scaled-up doll’s house, with two double-sided fire-places (still in use) and five interconnecting rooms (no hallways at all). But every roofline towers above you when you are child and every space feels cavernous. I visited again just after I was married – the new owners were happy to let me and my wife in to look around as they had just put it up for sale – and cracked my head on every doorframe before I worked out just how low I had to duck to pass through them unscathed.

In the long summer evenings when twilight stretched out past dinner, past bedtime, I remember sitting in the peach tree in front of the house, trying to jump from higher and higher branches. I don’t think I ever got higher than the third branch before my courage, or recklessness, gave out. During summer holidays I remember scrambling down the rocky slope behind our house to the grandly-named Jordan River below, first just with friends and then, increasingly, with my kid sister, Esther, in tow. We would see snakes sunning themselves on rocks along the path or slinking back into their hiding places of bush and rock. Entering up to our chests into the shallow waters of the Jordan, we would scoop out clay from the river bank to shape lumpy, organic pots that dried in the sun and then cracked and fissured pleasingly when we picked them up and moved them around. The parts we had been able to press flat, forming into a thin shell, would split or chip off cleanly, but the rest of the mass would fold and distort, revealing the moist clay beneath the flaky surface.

Or we held together twisted strands of overhanging willow branches and swung in low arcs on the little islets that dotted the river’s course.

My older sister and her friends turned the bonnets of abandoned cars into rafts and floated all the way down to the bridge a couple of times. But that was an activity for teenagers, and I wasn’t invited.

There was one time when Esther and I came across a length of fence-line that had been uprooted and let dangle – star-pickets, wire and all – over a rough cliff-face above a section where the river pooled and the soft sandstone had been scoured into depressions of varying depths. The ladder formed in this way was too clear an invitation to turn down. Esther, who was maybe four or five at the time, held on to the narrow wire ‘rungs’ and I manoeuvred around her, placing my hands and feet on the oustide of hers, enclosing her inside my body. Together we crabbed our way down the fence, stopping halfway down the cliff to rest inside one of the depressions. Cave is probably too grand a word – we were in no way hidden from view if anyone had been there and cared to look in our direction – but the notion of having found shelter in the midst of a great adventure gripped me.

Reaching the bottom, we dropped leaves and twigs into the river to watch them skitter through narrow races of stones, fetch up in the fragile hazards of fallen branches and twigs, or eddy their way out into the current and off to we didn’t know where. Brighton? Bridgewater? Hobart? The sea?

After a while, we made our way, koala-climbing up the fence again, back to the upper paddock and returned home.

The opposite block was vacant the whole time we lived on Marlborough Street. There were shabby, feathery clusters of fennel at its edges and in the drain that ran along the bottom of the street which left you smelling like licorice wherever you brushed against them. A kind of gorse, or some other low, woody bush, had colonised the block. Impenetrable from above because of the spiky leaves and upper branches, the twisted trunks and lower stalks of these bushes formed passageways that with only a little effort, I could force my way through. Playing hide-and-seek in this arena opened up almost infinitely ramifying possibilities as we traced along these hidden paths.

There were other places we played, too. The abandoned service station whose hollowed-out interior was a warehouse for hundreds and hundreds of possum skins. I don’t know who caught them, why there were stored there, or what was ever done with them, but I remember making my way in through a boarded-up window and clambering on the slippery piles of skins, breathing in the heady naphthalene scent. The old barn and the quarry near the old Georgian terraces – barracks for the soldiers who’d been stationed in Pontville – where my friend Roger lived. The churchyard. The showground.

I remember talking incessantly to any adults who crossed my path. Pontville was a tiny town on the Midlands Highway, north of Hobart, so there weren’t that many it has to be said. At the edge of the vacant block was a standpipe for distributing water. Water trucks would refill here and – as a three or four year old – I would go out, dressed in underpants, gumboots, rubber washing-up gloves and with a towel tied, cape-like, around my neck, to talk to the tanker driver. There are no photos. Don’t ask.

Or I would spend afternoons on the porch of the great sandstone house at the top of the hill, perched right next to the highway. As with the grand-sounding River Jordan, there was no dual-carriageway or multi-lane and even precious little shoulder to the Midlands Highway. Two lanes, no median strip and, owing to a steep descent and sharp bend on the approach to Pontville, every vehicle that entered would be slowed to almost a crawl. I would sit with Rick Steele, the house’s owner, and talk. After every dozen vehicles or so had passed by, we would both yawn extravagantly, trying to make the occupants of the next car to pass by yawn along with us. We rarely failed to get some sort of reaction.

Sometimes on weekends, my mum and dad would go with friends for walks along tracks around Mount Wellington. I would run ahead, trying to find the perfect ambush point, a place from which to launch myself and try to frighten my parents. Once, I was startled by a wallaby, which moved in jogging bounces away from me through branches and undergrowth. Trying to follow, I was amazed at how fast and fluidly it moved. How did it not get tangled and caught in tree-limbs at every leap?

I remember borrowing every book on dinosaurs in the Hobart Library two by two, week after week, and bringing them home until there were no more to read.

We had TV in Tasmania at the time, yes, but only two channels – one commercial station, and the national broadcaster, the ABC. Of these two, as a child I was only allowed to watch one. Playschool, Sesame Street, The Goodies, Doctor Who, Blakes Seven.

I was almost ten, and in Melbourne, on the way to our new home in Albury before I saw my first McDonald’s.

File under: like fast food only slower | portrait of the artist in his underpants and with a cape

4 Comments

Add YoursA wonderful trip down memory lane. The man with the water tanker was “Rocky” Briggs. The original bathroom lean-to was made of beaten flat petrol tins (they were rectangular in profile) nailed to the wooden frame. I found an abandoned house near New Norfolk and demolished and cleaned 12,000 hand made bricks to build the new “wing” with a bathroom, toilet and another bedroom and a long entrance hall. What beautiful memories.

It’s a great photograph of yours too. But the lean-to has already been replaced by the new additions. I remember the bricks being brought home to build it.

My partner martin and I are looking at purchasing this house as our first home. its been amazing to stumble across this page and read about the great memories had there. Thank you so much for sharing. I was always curious about the bathroom “wing” anyone know when it was built?

Hi Jamie, I think it was built in 1976 or 1977. My dad went and collected bricks from demolitions of old homes for months so he could build it with authentic materials.