The standard, modern army performs three principal functions. First, seizing pieces of real estate that someone has taken a fancy to. Second, stopping others seizing the bits of landscape they’ve taken a fancy to. And, finally, piling up sandbags to stop things getting very, very wet when it just won’t stop raining. Also, shooting people who want to borrow things that have been left behind the sandbag barriers after everyone has been evacuated to higher ground. Though this, in the final analysis, is merely a domestic and natural-disaster-related variant of function two, above.

Archaelogical evidence suggests that ancient armies performed pretty much the same tasks, only with soldiers dressed in togas, ephods, kilts or loin-cloths. Adequate ventilation and unrestricted movement for a soldier’s man-bits was, of course, more important in ancient warfare.

I refer to the standard, modern army advisedly, of course. The decidedly non-standard modern Swiss army – in addition to the three functions already noted – is regularly pressed into service to open cans and bottles, uncork wine, remove stones from horses’ hooves, strip wire, open letters, peel fruit, scale fish, perform manicures and improve dental hygiene. It is fair to say that the extraordinarily low rates of tooth decay enjoyed by the Swiss are the envy of the world. However, this kind of mission creep has generally been regarded as suboptimal by military planners.

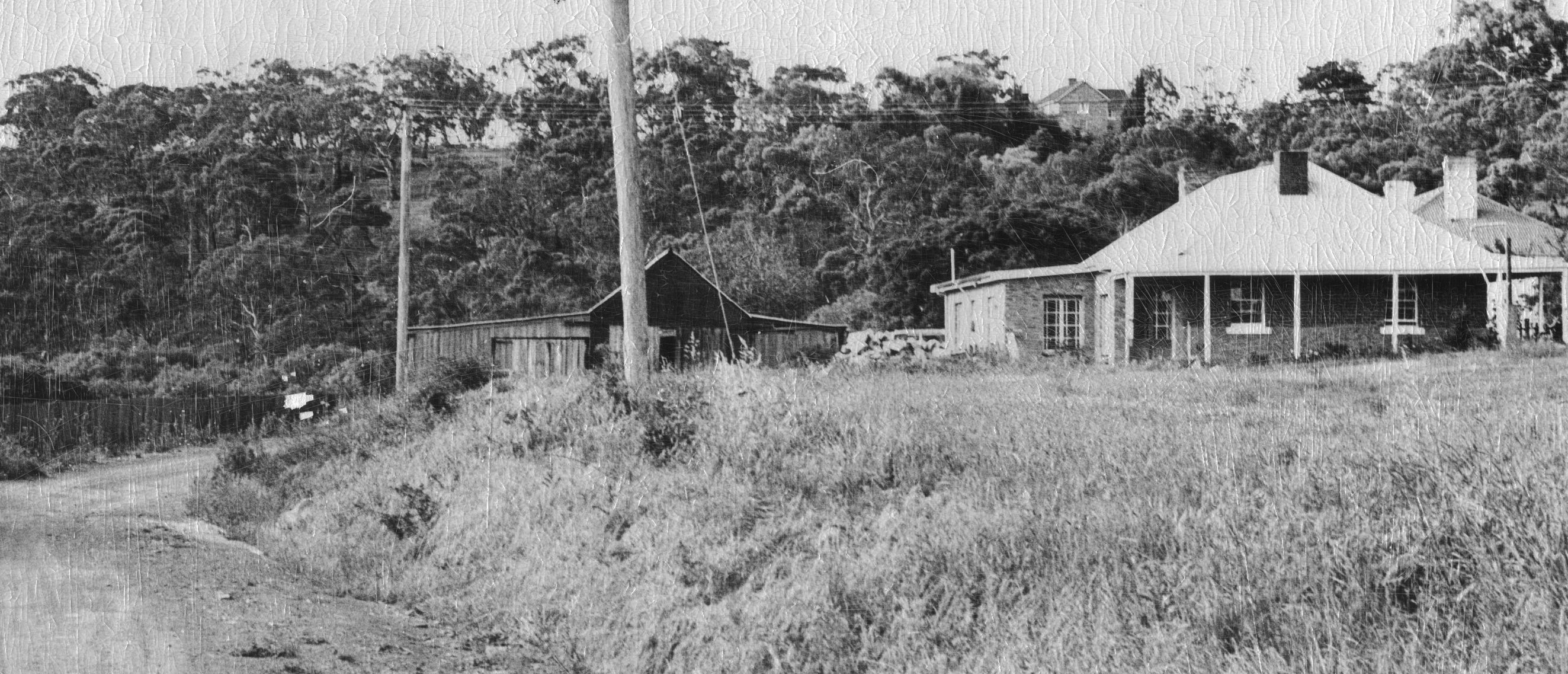

More selective in its rules of engagement, the Australian Army has – since its formation in 1901 – performed modern military doctrine’s three principal functions with distinction. And almost always in trousers.

At the time of federating the former British Colonies into a single Commonwealth of Australia, it was felt – not unreasonably – that there should be one body responsible for defence of the new nation in place of each colony’s separate forces. It was little remarked at the time that just such a body had previously existed and had been vigorously assaulted by the forebears of the very men now establishing the Commonwealth. It is reasonable to speculate that this was largely because the earlier Australian army, constituted in small bands to defend the land against invasion, was entirely composed of people whose Aboriginality rendered them unfit – according to well established legal and moral theories of the time – to claim ownership of a nation no matter how bloody long they’d been hanging around.

These moral and legal theories were remarkably robust in the face of roughly 50,000 years of unbroken Indigenous occupation of the land and were of a piece with contemporary opinion about the desirability of federation and the importance of defence. Howard Willoughby, writing in the Melbourne Argus in 1891, urged that “Australia must be substantially reserved for the occupation of the European race” and “that the inferior members of the human family should be here only to fill up insterstices in the community.” Defence, likewise, was necessary to “guarantee purity of race and constancy of possession,… inasmuch as otherwise some northern colony, tempted by the desire to turn its estates to immediate account, might let in Mongol or Malay wholesale, with complications that are too obvious to need explanation.”

At this historical remove, the complications might no longer be too obvious to need explanation. An educated guess suggests that the complications arising from the wholesale arrival of Mongol or Malay would have included upward pressure on interest rates, rapid demographic change leading to difficulties for government in infrastructure planning and service delivery, and an unexpected (though not necessarily unwelcome) broadening of culinary options among the general populace.

The man chosen to be the new Australian Army’s first commander was the experienced, and decorated, Major, General, Sir, Edward, Hutton. Earlier in his career, while serving as General Officer Commanding the Militia of Canada, Hutton had earned reknown by signing Canada up for the Second Boer War. Since he had done this by publishing mobilisation plans in the Canadian Military Gazette and not – as was more traditional – by actually discussing it first with the country’s civilian leaders, the letter of thanks from Great Britian came as something of a surprise to the Canadian Government.

With the all-important issue of the army’s command settled, other, more mundane, matters could also be attended to: uniforms, insignia, pay grades and the like. In a resounding blow for common sense, it was agreed right from the start that the Australian Army should not be paid in rum. Or, indeed, any alcoholic beverage. That had, surprisingly, not worked out well the first time.

File under: modern military doctrine | ante-natal classes of a nation |

(Image source: Museum Victoria)

1 Comment

Add YoursBen great post with well woven humour ans satire.